NOLA Blue Carbon

Community Project

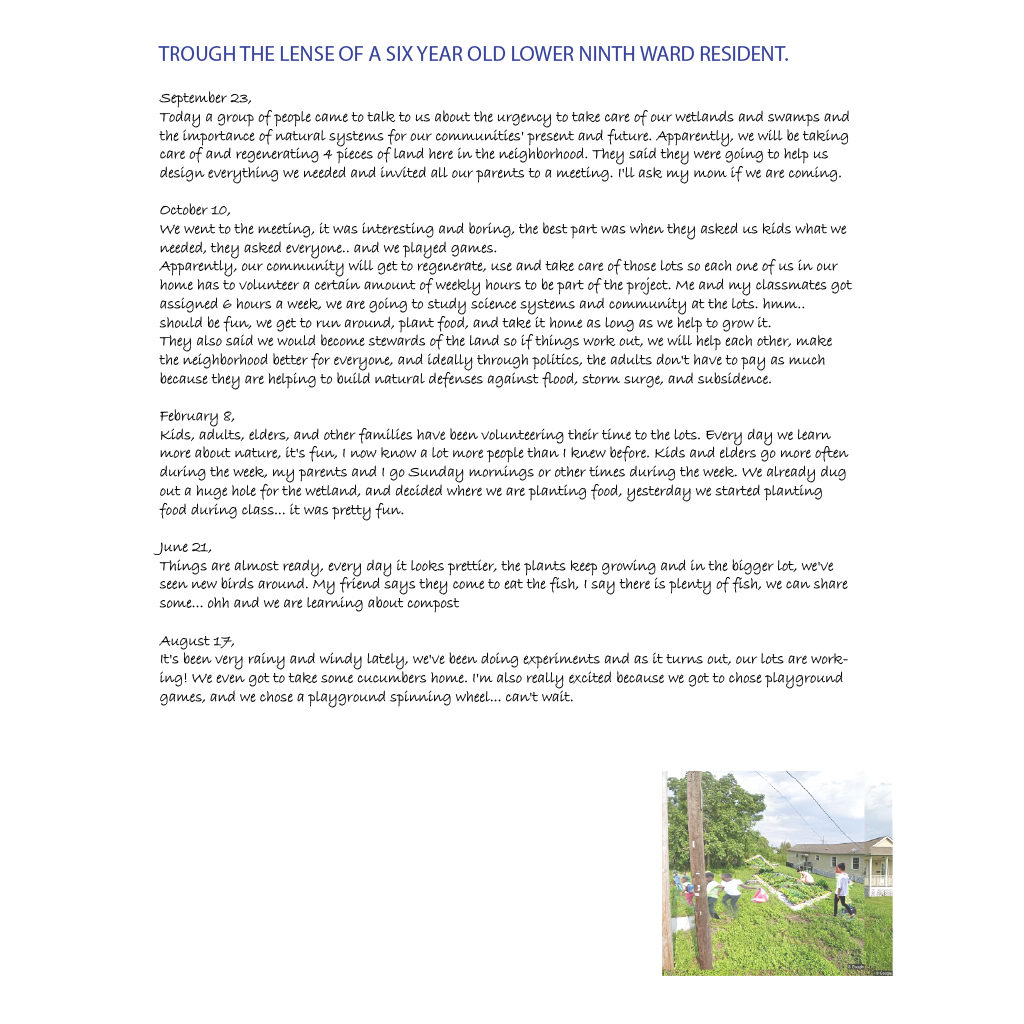

NOLA Blue Carbon Community Project focuses on eco-diversity, natural ecosystem regeneration, and community resilience in the Lower Ninth Ward. The project responds to nine objectives my studio group, our instructors, and I explored. The objectives divide into People and Communities, Ecology and Materials, and Structures and Engineering.

People and Communities:

- Foster safe, affordable, and welcoming environments that explore youth’s social and personal development opportunities.

- Shift power back into the hands of communities by addressing oppressive structures, systems, and spaces.

- Incorporating local forms of knowledge, people-to-land relationships, and any domain knowledge/strategies in a culturally and linguistically competent way.

Ecology:

- Foster new habitats and minimize displacement of existing wildlife which supports the growth and stability of local biodiversity.

- Prioritize ecological well-being and biodiversity through extractivist human practices mitigation by shifting importance back to the hands of Natural processes.

- Acquire a thorough understanding of the current local ecosystem of New Orleans through research and science to promote future sustainable building practices.

Materials, Structures and Engineering:

- Incorporate and prioritize the use of local materials that can be safely extracted, used and recycled on-site.

- Design structures that primarily consider local communities, local ecology and site conditions to guarantee equitable requirements for all ecosystem entities, including vulnerable minorities.

- Encourage the transition from hyper-control water mechanisms to natural water control mechanisms feasible from the individual to the community scale.

This project originates from socio-political materials and urban analysis of NOLA Port Lands earlier in the semester. It is the product of a study prompted by the objectives above, a gained understanding of deltas and New Orleans’ prominent water urbanism history and current challenges. I decided to start my study around a tangible water issue that will become more prominent in future years: flood. It is worth noting that other forms of water issues in Nola are under vulnerable “control,” such as water pumping and storm surge defence mechanisms. As a result, other water issues have emerged over time, such as the case of subsidence.

Studio participants: Abir, Alex, Cheshta, Jay, Juan, Nadisha, Razi, Victoria and myself – Alejandra. Studio Instructors: Catherine Bonier and Aaron Chang. Additional collaborators: Ana and Ian.

Study

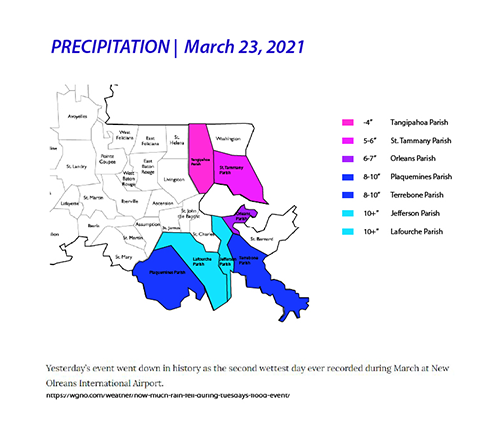

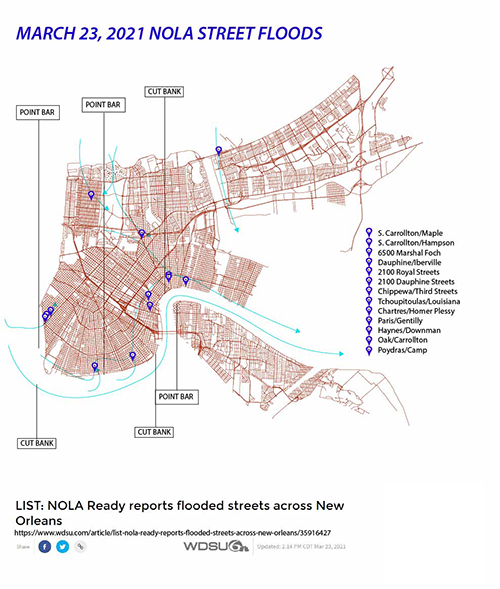

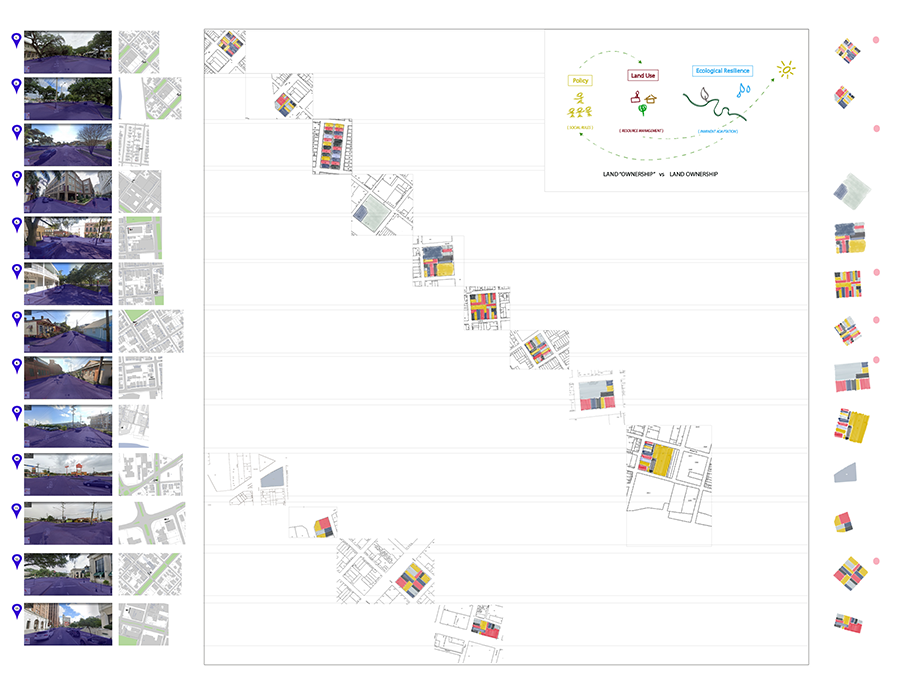

On March 23, 2021, there was a high precipitation record. I found regional information and Nola local information. Flooded streets were reported throughout the city, especially around high areas due to surface impermeability and high-water tables. I mapped the recorded locations to analyze further. Based on previous studies and concepts around policy, land use, and ecological resilience. I decided to physically separate land properties from the flooded site’s urban typologies — which led me further to ideas around eco-diversity, community resilience and land stewardship.

“…eco-diversity, community resilience and land stewardship.”

Project

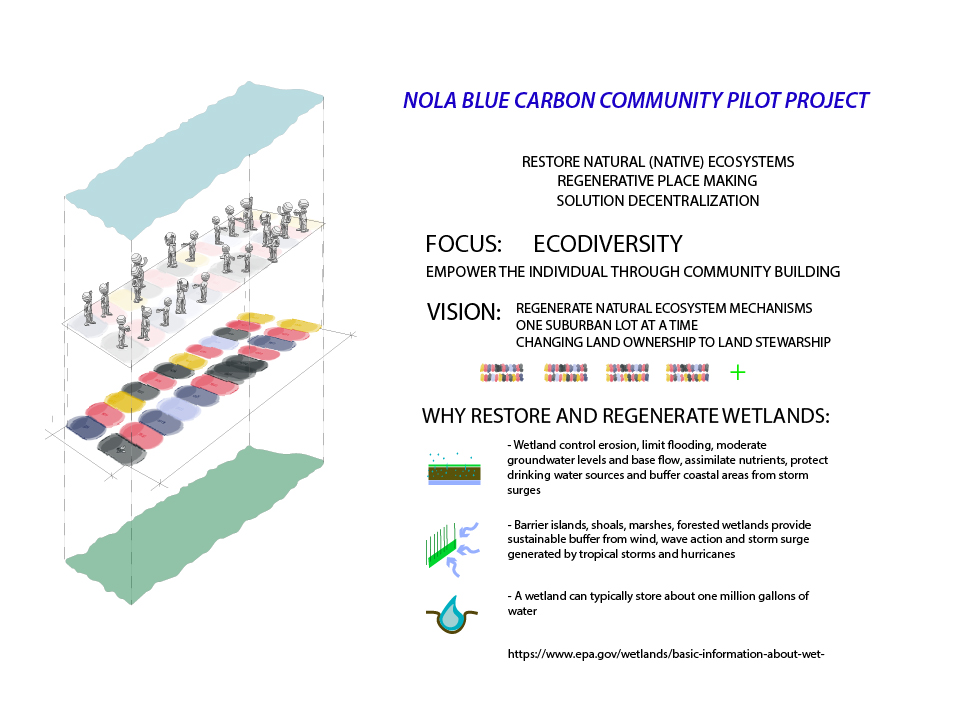

NOLA Blue Carbon Community Pilot is a project that aims to restore natural ecosystems through community processes and regenerative placemaking. The goal is to progressively create strong and resilient communities that have agency over third space land use. These communities will focus on eco-diversity-based resilience strategies. Ideally, developing and implementing these strategies will increase personal, ecological, and social agency. Suburban typologies are prominent in North America and land-rich countries. This project asks: what if environmental and community resilience efforts contrate on suburban typologies? Can we change land ownership patterns to stewardship patterns through community enhancement efforts? Can suburban residents become land stewards and proactive resilience agents? Will communal and land stewardship benefit them economically, socially, and ecologically?

In the past, the NOLA area was a series of swamps, marshes, and wetlands. Wetlands and swamps control erosion, limit flooding, moderate groundwater levels and base flow, assimilate nutrients, protect drinking water sources, and sustainably buffer coastal areas from storm surges, wind, and wave action from tropical storms and hurricanes. They can typically store about one million gallons of water. Nonetheless, colonizing efforts disarmed natural coastal balance and defence mechanisms. Therefore, restoring these biological mechanisms is crucial to Nola and Southern Louisiana community resilience.

Infrastructure Strategy

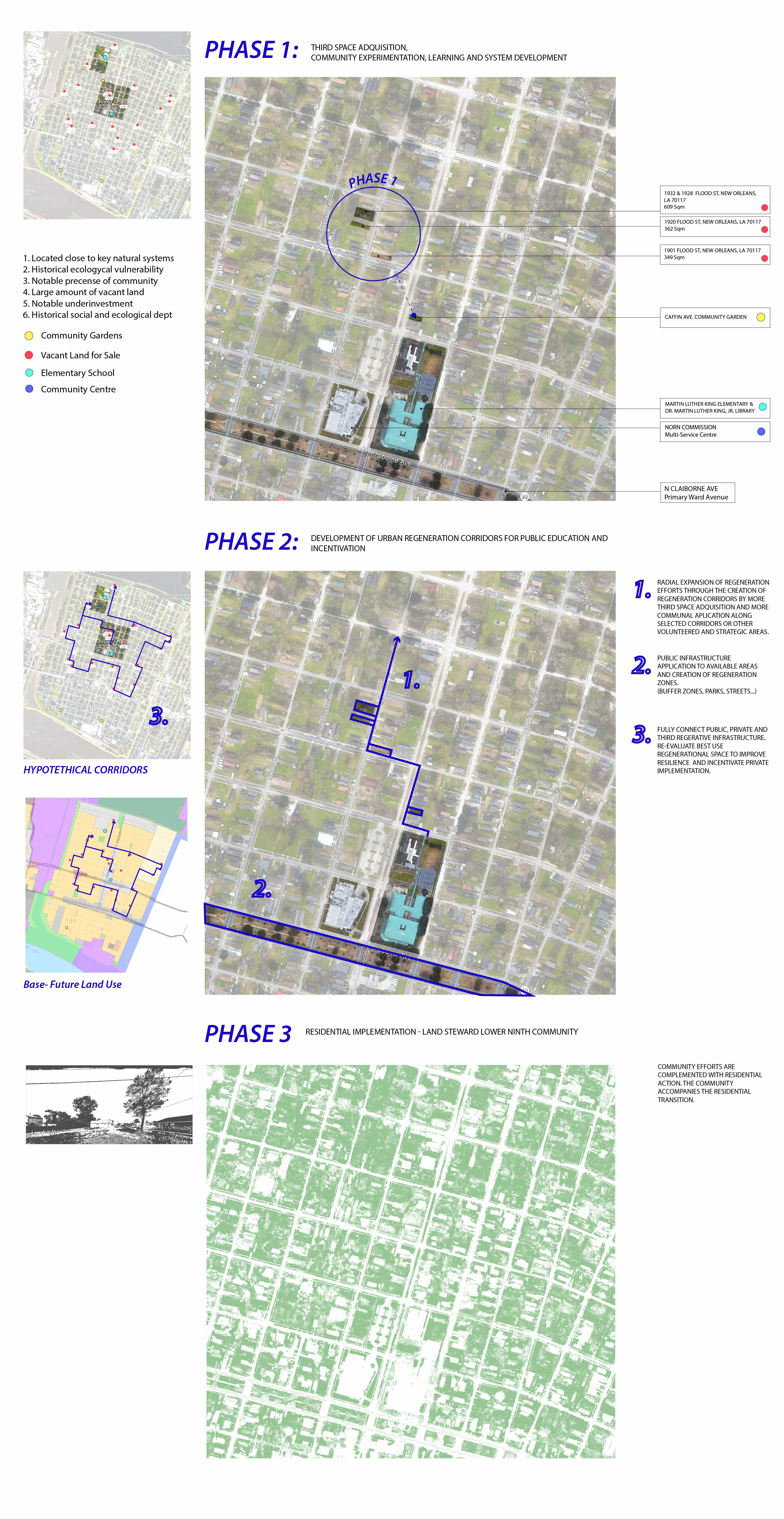

For this analysis, I mapped the Lower Ninth Ward’s community gardens, vacant land for sale, educational centers, and community facilities. The site selection derives from the following rationale: First, it is close to historically vulnerable vital natural systems. Second, it has a strong community garden presence and large amounts of vacant land showing notable underinvestment. Thirdly, there is a traditional social and ecological dept to this area.

As time is a critical factor in progressive natural regeneration, this project consists of three phases:

PHASE 1:

The First Phase of the project would involve vacant lot acquisition. I decided to focus on four lots due to their proximity to community gathering centers. In the first Phase, this vacant land passes to the community as a third space for natural systems restoration, experimentation, learning, and systems development using Biden’s community budget. Once the community has been able to create replicable systems, the second Phase will begin.

PHASE 2:

The second Phase will be about developing urban regeneration corridors for public education and incentivization. It will start by radially expanding the regenerative systems to volunteered and selected passages through more third-space stewardship. Then, public infrastructure implementation in the form of regeneration zones along parks, streets, boulevards, and buffer zones would follow. Finally, for the optimal efficiency of these systems, the goal is to connect public, private, and third-space regenerative infrastructure and re-evaluate the best use of these regenerative spaces for the benefit and participation of all.

PHASE 3:

The third Phase concerns the maintenance and incentivization at the residential level and the continuation of the previous phases’ efforts. After Phase 1 and 2, if the community has seen positive results, more integration, and social-economic incentives, the goal is to sprawl these ecological resilience efforts at a residential scale to increase natural resilience and benefit all.

Community Strategy

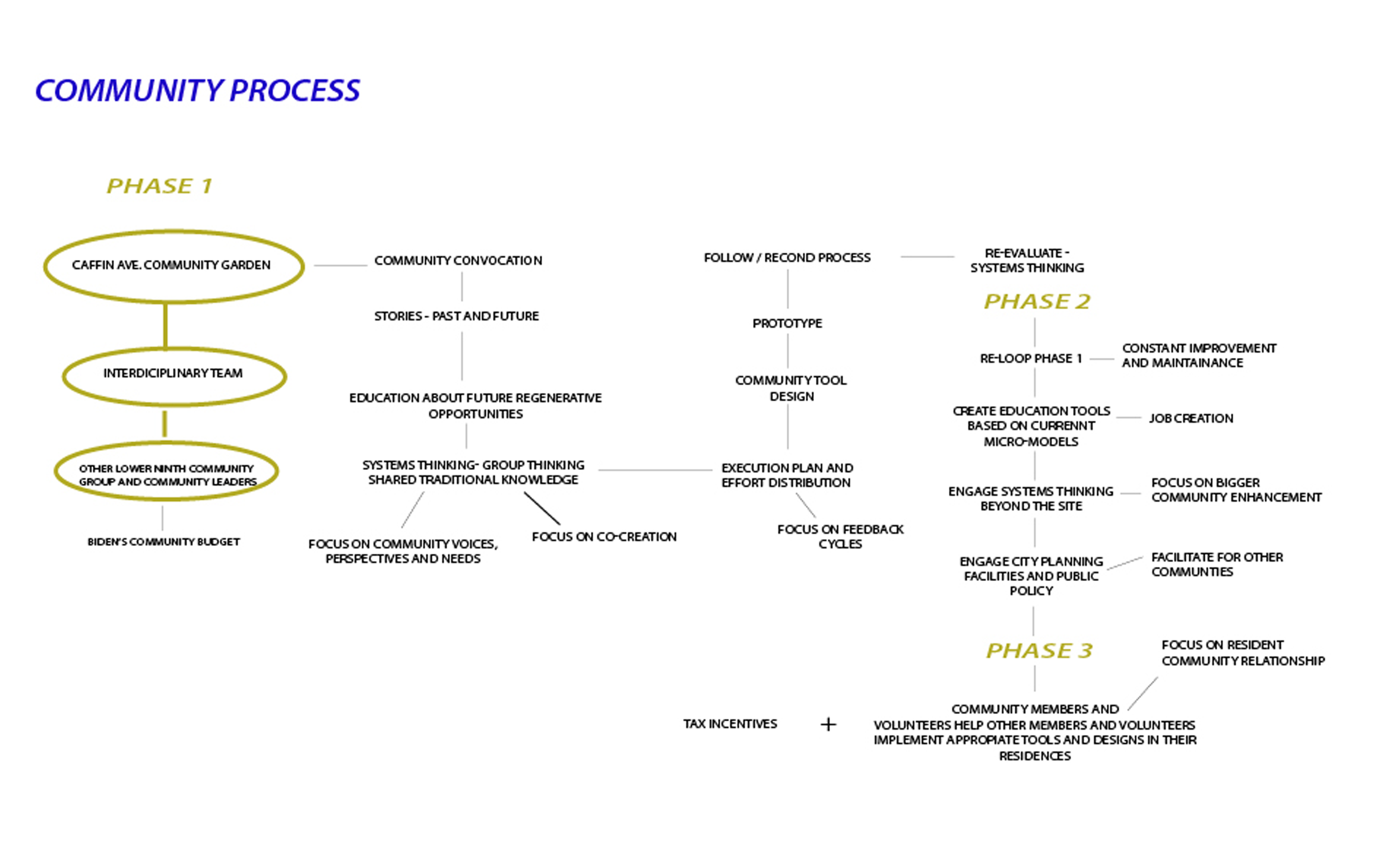

Human process planning is essential for a bottom-up approach like this. Therefore I also developed a three-phase community strategy:

PHASE 1:

Ideally, Caffin Avenue Garden, an interdisciplinary team, and other Lower Ninth community groups and leaders convocate the community to share stories about themselves and their neighbourhood to understand what improvement looks like to them and align goals further. Then, educational meetings focused on community integration and co-creation to develop holistic systems with multiple perspectives would begin. Then, we would plan the execution of those systems and effort distribution among the community emphasizing cyclical patterns. After that, we develop design tools, prototype, follow the process, re-evaluate, and re-loop as necessary. Once these efforts are replicable, a similar approach to Phase 1 above would begin.

PHASE 2:

The second phase focuses on improving and maintaining effective systems, creating educational tools, job creation, and engaging a larger community beyond the chosen four sites, including city planning facilities and public policy. The community members would facilitate this process for themselves, other communities, and larger entities.

PHASE 3:

Lastly, the third phase will be about community and labour maintenance by helping other residents implement appropriate learned tools in their residences, enhance community relationships, and create more tools and education efforts to develop land stewardship tax incentives.

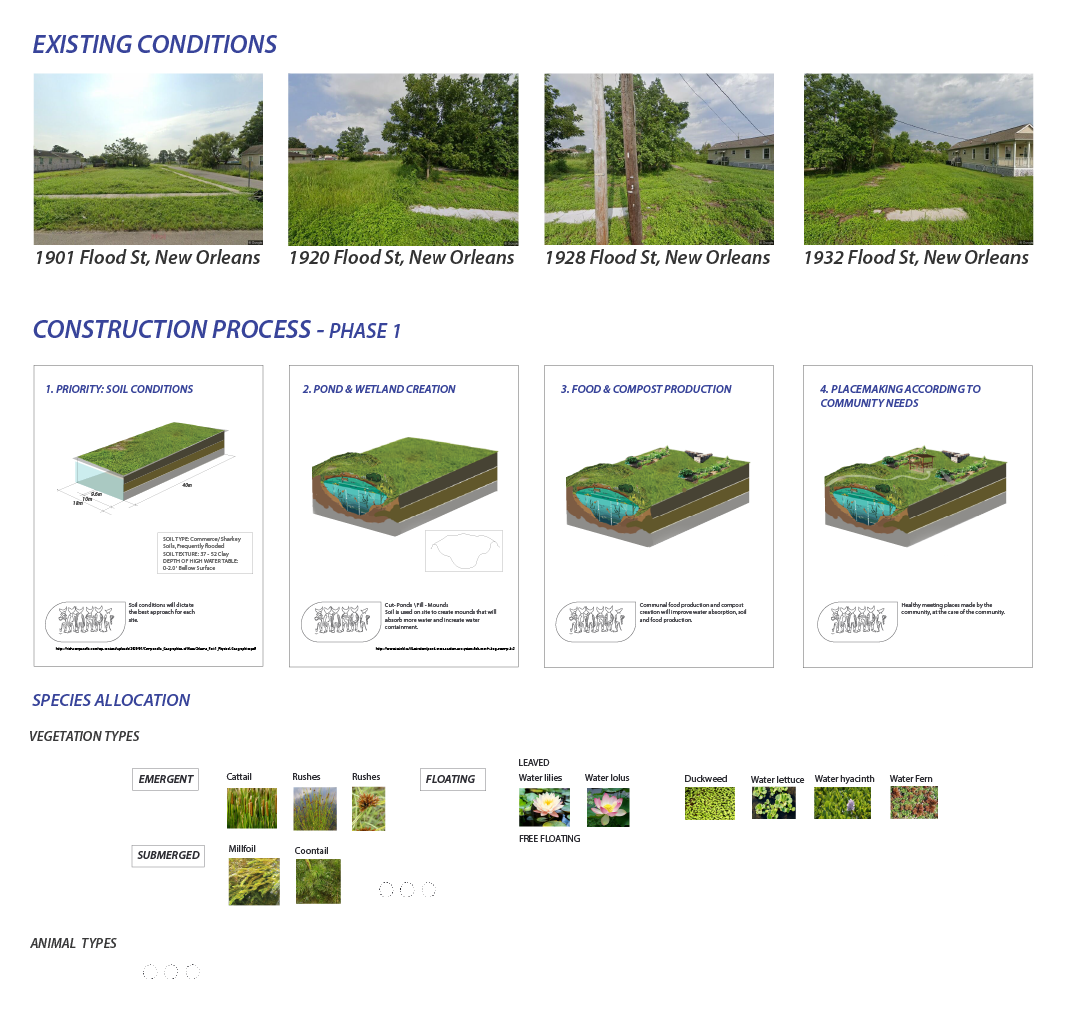

Ecology

The timing of natural regeneration and community processes is unpredictable, so I started with phase one implementation guidelines. Ideally, regeneration practices begin with a deep understanding of soil conditions, water tables, temperature, humidity, etc. Fundamentally soil conditions will dictate the best approach for each lot. The goal is to create natural structures providing water containment and filtration-like swaps. Hence, I decided to focus on ponds for wetland effect re-creation and mound creation with the soil cut around these structures to increase water absorption. A key factor about these third spaces is that since NOLA soil is fertile, and the lower ninth community remains disconnected, food and compost production would positively affect the community. Compost production is a great way to deal with our residue; it improves the gardening process and fundamentally creates new land that can be added on-site layer by layer in the same way swamp sedimentation enhances soil structure.

Finally, the local community stewards these third spaces, so placemaking based on community needs is essential to strengthening the community and the natural systems.

Experience